Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

-George Santayana, The Life of Reason

I am reminded that today is Holocaust Memorial Day. 76 years ago Allied forces liberated the remaining Jews from the Auschwitz concentration camp. Awareness of the depths of the evil unleashed on the world by the Shoah has been a part of my worldview since I was a young adult. My father gave me my first copy of Elie Wiesel’s Night when I was in high school and my eyes were opened in a way that shattered whatever cocoon of privileged safety I had erected around myself in the first decade and a half of my time on this planet. Since that time, I’ve probably read Night a dozen times. Elie Wiesel became my hero and that adoration reached its zenith when I had the chance to see him speak at a rally for meant to draw attention to the ongoing genocide in Darfur. While George Clooney, Nancy Pelosi, and a freshman Senator named Barack Obama all spoke to great acclaim from the crowd none of the electricity generated by the group of people gathered in the center of the nation’s capital compared to awed reverence that consumed the 10,000 or so of us on the Mall when Elie Wiesel stepped up to the microphone. I remember against a backdrop of a holy and haunting silence in which one could hear a pin drop, his elderly voice, strained from the years, saying, “Good afternoon. I’m Elie Wiesel.” as if nobody would know who he was otherwise. In his words that day he kept his end of the bargain for those who had gone before him by linking the experience of the loss of six million Jewish lives in the Holocaust with that of death of three million Darfuris in the Sudan.

In seminary, under the tutelage of my professor (and later doctoral advisor), Stephen Ray, the Holocaust became the lens through which I viewed the theological work undertaken by the Christian Realists, so many of whom were either in Germany or traced their lineage back to the Germanic tribes that dwelt in the northern part of the Holy Roman Empire. One of those native thinkers, the theologian, Paul Tillich, became my closest companion during that time—his theological work dramatically impacting my own reflection while his radio dispatches broadcast back into Germany during World War II calling for Germans to rise up again the Führer, formed the foundation of my Masters Thesis on the religious dimensions of the Holocaust. Once complete, it was dedicated, in part, to Elie Wiesel.

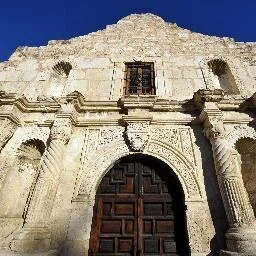

Collective memory is an important thing within any culture. I was reminded earlier this week while working on the Washington Post daily crossword puzzle of the refrain “Remember the Alamo.” The phrase was used to unite and inspire the soldiers who fought in the Texas Revolution for the then “Republic of Texas.” It was a rallying cry shared between this soldiers following the Mexican siege against a fortress named “The Alamo.” After the fall of the Alamo those Texian soldiers brought the fight back to the Mexicans in the early morning blitz attach known as the Battle of San Jacinto. The slaughter lasted all of 18 minutes as the Texian soldiers shouted to one another to “Remember the Alamo” as the exacted their revenge. Collective memory can be an exceedingly powerful force within a community or collective.

Within the Jewish community and faith, there is a similar mantra woven into their story, a Northern Star by which they are guided as they traverse into each new moment. It is repeated at Seders and passed on like an inheritance to each subsequent generation of Jewish boys and girls—a call to remain vigilant against forces that might seek to do harm to the Jewish faithful. With the full weight of a tragic history undergirding it, they intone the words, “Never forget.” Never forget the enslavement and forced labor at the hands of the Egyptians. Never forget the series of exiles brought on by the Assyrians and the Babylonians. Never forget the diaspora that ensued after the Roman Empire swallowed their tiny strip of land with an outsized coastline on the Mediterranean Sea or the acceleration of the “dispersion” of Jews following the sacking of Jerusalem and the Temple in 70 by those same Hellenistic forces. Never forget the anti-Semitism of the early Chrsitian church, the monstrous mythology that developed around the Jewish people in the Middle Ages that told tales of canibalism and stealing of Christian children that they might ritualistically drink their blood. Never forget the experience of Russian pogroms in the 19th century in which thousands of Jews were slaughtered by those loyal to the Tsar. Never forget the accusatory “Stab in the Back” by the native German people following their defeat in World War I. Never forget the Beer Hall Puscht, or Kristallnacht, or the forced expulsion, or the ghettos, or the separations, or the cattle cars, or the wailing, or the concentrations camps, or the ovens. Never forget.

In Night, Wiesel writes,

For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living. He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.

Each one of us owes a similar debt it to those who have come before us. It is incumbent on all of us to tell the collective story of the fallen as part of our own, to never forget the devastations of the past lest we fall into the trap that the philosopher George Santayana warned us about—that we repeat our history again and again—and to be vigilant when virulent hatred arises as it numerous times in the past 76 years. To never be silent in the face of injustice, or pain, or suffering, or hatred but to open our mouths and speak out. To put one foot in front of the next and walk with those who march for greater justice, wholeness, peace, dignity. To never again allow the gathering winds that inspired the hatred and finality of the “solution” to the Jewish “problem,” conceived of in the National Socialistic Germany, to resurface again be it under different banners, or slogans, or clothing, or guise or leader. In this, we are all responsible.

The world is smaller than it as ever been. Virtually nothing can occur in the world without the rest of the planet having some sense of its happening. But, with this awareness comes a responsibility, an obligation owed to those who have come before whose wicks were extinguished far too soon in this life that must be met, and a calling recognized by all of the major religious and secular movement over the past three millennia. We are responsible for sowing seeds of love in soil that has been tilled by hatred, to work for peace in the face of cycles of violence that have been allowed to spin unencumbered for much of human history, and to be bearers of hope in a hopeless world. That is the task of all the members of the human race and we only ever fail when we forget those who have come before us—their successes, their failures, their rising, and their falling—and the only remedy for this illness is to follow the lead of our Jewish brothers and sister and always remember, and to never, ever forget.

On this 76th anniversary of the end of the Holocaust, may we rededicate the work of the whole of the world to honoring those who have come before us by doing the work that they themselves could never do. Let us be light in a shaded world.